I pray one day, we will finally feel at home: Hannah Drake reflects on time in Toronto, Canada

“I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything. The sun came up like gold through the trees, and I felt like I was in heaven.” Harriet Tubman

I have read this quote by Harriet Tubman many times in my life; however, it was not until I stood at Niagara Falls, engulfed by the midst, the sky a shocking shade of cobalt, with waterfalls all around me, that I believe I had a sense of what Harriet spoke of. Just across the river was Canada, a new home, a new country, a new place to be free.

When Josh and I visited Toronto, we walked around the neighborhood, which reminded me of a mixture of Brooklyn brownstones colliding with Victorian-style homes of Old Louisville in Kentucky. We stopped at a coffee shop that sold old-school records with a sign at the door that set the tone that this was a place that was inclusive of all people. I ordered an expresso because that is what you do when you want to be fancy in a new city, and we sat outside as if we belonged there. Something about this place seemed different.

We walked to an eclectic shopping district called Kensington. There, I spoke to a Jamaican shop owner with locs that hung to his ankles. He politely extinguished his Swisher before telling me about all the benefits of moringa oil. Next door, I bought a ring from an Asian woman with a yin and yang symbol to remind me of the two forces within me that are always at play and that need to be balanced for me to be in harmony. It is easy for my equilibrium to falter when I study the atrocities of enslavement. With history comes tears of sorrow and anguish, and I often find myself angry. But I cannot remain in the darkness. I must always search for the light because I know it is there.

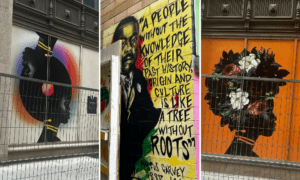

I placed the ring on my finger while walking in the neighborhood. I took a picture of a mural of Marcus Garvey near a stand selling fresh fruit. There were so many cultures gathered in this area, welcoming you to come in and say hello. We entered a store that sold jewelry and stones. I saw a ring with a paw on it that I wanted to purchase for my daughter. As I went to pay, the shopowner was outside of the shop speaking to other patrons. I had experienced that before. In Senegal, when I went to purchase earrings and, the shopowner was outside. It wasn’t until that moment that it dawned on me that it was not a crime to be Black because almost everyone was Black, so race being associated with criminality like it is in America was non-existent. But here in Toronto, unlike in Senegal, the shopkeeper was a young white woman. Yet she was not concerned about me shopping. She didn’t follow me around the shop. She assumed I was like any other shopper browsing and my skin color was not a factor. I bought the ring, and she wrapped it up in a brown paper bag and smiled as we left.

We continued walking, and I tried to carry on a conversation with Josh. Still, at the same time, my mind was having this inner dialogue as I walked by so many different races and ethnicities. Different cultures, food, and accents were all around me. And I was just walking. I was just existing, and no one cared. I hadn’t had that feeling since 2016 when we visited Senegal. I realized the trauma that Black Americans have faced is so pervasive it is like a cloak that you wear every single day. And every day in America, that trauma is reinforced with laws, policies, people calling 911 because you merely exist, and the seemingly endless social media posts of Black people being murdered by the police or vigilante citizens. Every day of existence in America is a day filled with trauma. There is never a moment to just breathe because America works overtime to remind you of what it thinks about you as a Black person. As James Baldwin wrote, “You were born where you were born and faced the future that you faced because you were black and for no other reason. You were born into a society which spelled out with brutal clarity, and in as many ways as possible, that you were a worthless human being.” I carried that trauma with me to Canada with the expectation that Canada would treat me as America does. And while I am sure Canada grapples with its own racial reckoning, what happened to Black people in the United States is so uniquely American. Dr. Joy DeGruy, author of Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome, has coined the term by the name, which is a theory that explains the etiology of many of the adaptive survival behaviors in African American communities throughout the United States and the Diaspora. It is a condition that exists as a consequence of multigenerational oppression of Africans and their descendants resulting from centuries of chattel slavery.

I realized I was walking around Toronto carrying the adaptive survival behaviors that I had acquired from being Black in America. When I packed for our trip, I made sure to carry all the things I thought I would need and checked and rechecked my backpack to make sure I had my passport. I didn’t realize that I was also packing survival skills for being Black in America, and in Canada, I finally felt the weight of how heavy those skills are – the detriment on my physical, mental, and spiritual health from carrying those skills around for decades. Similarly to my time in Senegal, I wanted to pause and enjoy the moments of freedom. I dined in a fancy restaurant and laughed with Josh as we ate ceviche without a care in the world. I walked into a store and calmly browsed, not feeling that all eyes were on me. I exited the store without buying anything and didn’t feel someone would accuse me of stealing. I took it all in because I knew I would return to America, return to ground zero of my trauma. It was always there to greet me and say, “Welcome back home. We have been waiting for you.”

I remember the author of I’ve Got A Home In Gloryland, Karolyn Smardz Frost, was telling us about the lives of Thornton and Lucie Blackburn, who fled Louisville, Kentucky, and sought freedom in Toronto said, “America’s loss was Canada’s gain.” Her words still sit with me today and will continue to stay with me for the rest of my life. I often think of all that America lost and continues to forfeit because we refuse to face our past.

I enjoyed my time in Canada; however, it saddens me that I must leave home to feel at home. I imagine that is how Thorton and Lucie and many other Black people who sought freedom felt, fleeing the only place they ever knew as home to find a place where they could truly be at home. Because home isn’t just a dwelling; home is freedom, and love and belonging. Something many Black people are still searching for in America. I pray one day, we will finally feel at home.